Time-stamp:<>

SECTION 1

ABOUT THIS BOOK

1.1

THE GOAL OF THIS BOOK

Reading this book will not turn you into a world champion auto

racer. It can help you become a better, safer driver whether you are

driving on the race track or on public roads. Unlike many books on

driving, this one was explicitly designed to be used in conjunction

with a

performance driving

school, taught at a racetrack. This book is designed to give you the

background that you need to get the most from every minute of

tracktime without going into so much detail that it would take forever

to read. It is meant to be an introduction to performance driving, not

the definitive text. There are many excellent in-depth books on the

subjects of

performance driving

, racing, and race car preparationand the material in them should be

helpful for any one who wants to continue improving their driving, or

progress on to racing.

Even if you are not planning on taking a driving school at a

racetrack, this book can help you improve your driving on the

street. The principles are the same, even if the opportunities to

safely explore the limits of handling aren’t.

1.2

STRUCTURE OF THIS BOOK

This book has eight major sections.

Section 1 ABOUT THIS BOOK

Section 2 BASIC PRINCIPLES

Section 3 ABOUT THE TECHNIQUES

Section 4 ABOUT THE ROAD

Section 5 ABOUT THE DRIVER

Section 6 ABOUT THE SCHOOL

Section 7 COURSE AND TURN DESCRIPTIONS

������������������������������������������

GLOSSARY

The

ABOUT THE CAR

section considers the subjects of traction and weight transfer. It

also touches on gears and gear choices and braking. Some familiarity

with the basic physics involved will make it easier to understand why

things work the way that they do.

The

ABOUT THE TECHNIQUES

section discusses how to get the car to do what you want it to.

Knowing the proper

line

is only part of the battle, you must beable to make the car drive that

line

.

������������������

The

ABOUT THE ROAD

section describes how and where to position the car on the road, what

is a

line

, what is a good

line

, why some

line

s are better than others, how to select the best

line

and combination of

line

s.

The

ABOUT THE DRIVER

section discusses those things that affect the driver and his/her

state of mind. Things that will improve or hinder your mental,

emotional or physical state on the track.

This book is meant to be used in conjunction with a driving

school. The

ABOUT THE SCHOOL

section discusses special considerations to be taken into account by

both the students and the faculty.

IMPROVING YOUR DRIVING

discusses analyzing your own driving so that you continue to improve

after you no longer have the supervision of an instructor.

There is also a

GLOSSARY

in the

APPENDIX.

If you run across a word or phrase that you do not understand, look it

up before you continue.

1.3

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

There are two sides to driving skill; knowing what to do, or the

intellectual, and the physical ability to do it, or the

kinesthetic. Knowing the

line

perfectly won't make you go anyfaster, if you can't actually drive

it. Having perfect car control won't make you go faster if you

consistently, deliberately, put the car in exactly the wrong place on

the track.

By learning and understanding the underlying principles of what you

should do before you get to the track, you will be able to devote your

full attention to learning how to do it once you get there.

While this book can be read in a single sitting, there is too much

material to absorb all at once. Give yourself several evenings so you

can read and understand a little at a time before going on to the next

section. Better yet, first scan through the book to familiarize

yourself with its overall contents, then go back and read each section

carefully, concentrating on a little bit at a time.

Treat this book as you would any textbook. Make notes and write

questions in the margins and on the diagrams...then when you learn the

answers, write them in next to the questions. If you do not obtain

this book in time to study it fully before getting to the track, read

the sections on

Line

(sub-section 3.1),

Attitude

(section 5.2.2) and

Flags and Signals

(section 6.2). You will also find it helpful to learn some of the

terms in the glossary.

1.4

A REQUEST FOR YOUR HELP

At the back of the book there is a short questionnaire. I need your

input to help me improve future editions. Your cooperation in passing

along your honest opinions will be appreciated.

Larry Colen

Felton, California

July 2003

SECTION 2

THE CAR

2.1

A SHORT NOTE BEFORE THIS SECTION

This chapter explains the basic physics behind balance, weight

transfer and traction. Many people find that this helps them get a

better feel for what is happening to the car as they perform the

various techniques described in this book. Other people are not as

interested in why taking their foot off the gas will cause the car to

turn more, it is enough for them to know that it does. I have

attempted to take an inherently complicated subject and present it in

the simplest possible terms. Read over this section. If you are the

sort of person who enjoyed their science classes in school, you will

probably find that it helps you understand why the techniques

described in the following sections work. If, on the other hand, it

just makes your brain hurt, skip on to the next section and don

’t worry about it.

Before I continue, I ’d like to give a quick explanation of the

drawings that I use in this section, or "What do all those funny

circles and arrows mean?"

The circles represent a concept called the "

Circle of friction

". If the circle is just by itself, or is drawn in the middle of a car

it represents the overall ability of the tires of the car to

accelerate, brake or turn. The arrow represents what the driver is

trying to make his car do. If the arrow is pointing forward he is

accelerating, backward he is decelerating, to the side he is

turning. If the arrow is completely inside the circle, the tires can

do what the driver is attempting. If the head of the arrow falls

outside of the circle, the tires will not be able to do what the

driver is attempting and one or more of the tires will

skid

.

If the driver is trying to accelerate (or brake) and turn at the same

time, the arrow will point at some angle that is not exactly either

front-back or to the side. To figure out what the arrow would be, draw

an arrow showing the forwards

acceleration

, now draw an arrow perpendicular to it showing how hard of a turn the

driver is trying to make. Draw two more lines that complete a box made

out of the first two arrows. Now draw an arrow that starts at the

corner of the box in the middle of the circle and which ends at the

corner of the box diagonal to the base of the arrow.

The term accelerate just means to change the velocity, either the

speed or the direction, of the car. So any time a car speeds up, slows

down or turns it is accelerating in some direction. The arrow is the

acceleration

vector. The direction that it points is the direction the car is

accelerating. The length is how hard the car is accelerating.

When I draw the circles at the corners of the car, they represent the

weight on each tire. The bigger the circle, the more weight there is

on that tire. Since more weight on a tire gives it better grip, these

circles can also be looked at as the

Circle of friction

for each tire. If a driver is trying to turn at one g and his front

tires can take 1.1 g of

acceleration

, but his rear tires can only take 0.9 g of

acceleration

, then the

acceleration

vector on the front wheels will be inside their circle of friction and

they will grip. The

acceleration

vector for the rear tires, however, will be outside their circle of

friction and the rear tires will

skid

possibly causing the car to spin out, this condition is called

oversteer

.

2.2

TRACTION, WEIGHT TRANSFER AND THE CIRCLE OF FRICTION

Ultimately, your tires determine the limits of your car's

handling. There is a concept used for describing the potential ability

of a tire. A circle which has a radius equal to the maximum force that

can be generated by friction between the tire and the road is known as

"the

circle of friction

".

For the sake of simplicity let's say that the tire can exert one pound

of sideways force for every pound of vertical force pushing down on

it. This is a somewhat simplified explanation of the technical term

referring to the tires ability to take one g. (If one pound of

downward force would only allow a tire to exert one-half pound of

sideways force (before the tire started

skidding

) it would be said to take one half or 0.5 g. In our simplified

example we will assume that the tire can sustain one g, accelerate at

one g (engine allowing), or turn at one g. If however, you are braking

at .7g, there is only about .7g left over for turning. (This is where

you could use the high school trig that you never paid any attention

to). Likewise if you are turning at .8g only .6g remain for

acceleration

. (Use the Pythagorean theorem to make the math work out)

This means that if you go hot and heavy into a turn, using all of the

tire's threshold braking ability right on the verge of lockup, and you

crank your steering wheel hard over your car will... continue to go

straight. There will be nothing left of the tires' abilities to make

the car turn.

There is another aspect to the friction circle. The friction circle

for each tire has a different size and shape which can be changed by

driving technique. But there is a catch: What you give to one is

taken from another.

For instance, the more force pressing down on the tires, the stronger

their grip on the road. The downward force is varied is by braking or

accelerating. When you brake, the car's weight shifts forward, putting

more weight on the front tires while taking weight from the rear

tires. This means that while the front tires hold better, the rear

tires hold less well, and the car has a tendency to

oversteer

. Similarly, accelerating shifts the weight to the back, causing a

tendency to

understeer

. (See section 4.6.4 for an explanation of under- and

oversteer

.)

So far the discussion has assumed a state known as "static"

friction. If you are trying to slide something, it takes a lot of

force to get it to move, but a lot less force to keep it

sliding. Under normal conditions, your tires are in a state of

"static" friction with the road. However, when they "break free" they

then go into a state of sliding friction where it takes much less

force to keep them sliding. This is why when you lose it, it seems to

happen all at once. The force keeps building up until it exceeds the

limit by a little bit. Then, all of a sudden, it is way above the new

limit and Whee! Your rear end comes around to ask you what you

thought you were doing.

Of course, if your car has enough

torque

, tromping on the gas causes whichever wheels are driving to start

spinning, losing traction at that end and causing the car to either go

straight off the road if it is a front-wheel drive car, or spin out if

it is a rear-wheel drive car.

<DIAGRAM circle>

Speeding up, slowing down, turning, and going up or down hill each

accelerate the car in some direction. When a car accelerates, weight

(and therefore traction) is taken away from the tires in the direction

that the car is accelerating toward and given to the tires the car is

accelerating from.

When cornering, weight is transferred from the inside wheels to the

outside wheels. During hard cornering, one of the inside wheels will

actually lift off the ground. If the suspension binds or bottoms out,

both inside wheels could leave the ground. When there is little or no

weight on the inside tires, especially in cars with stock suspensions

and performance tires, you can sometimes put them past the edge of the

pavement at the

apex

of the turn without losing traction.

When a car is speeding up, weight is transfered to the rear

wheels. Since the rear wheels always point the same direction as the

car (unless something has gone horribly wrong) the car will be more

stable. This is the reason behind the old adage "When in doubt, gas

it". Remember,

acceleration

is your friend.

When a car is slowing, weight is transferred to the front wheels,

making the car turn more. If overdone (especially in the rain) this

will cause the car to

oversteer

, or spin out.

When a car starts up a hill, or reaches the bottom of a hill, it is

suddenly accelerated upward. This transfers the weight to tires on

the underside of the car. Since all of the tires should be on the

underside of the car, they will all work better allowing more traction

than on the flat.

On the other hand, when a car crests a hill, weight is transferred

away from the tires and the car will not have as much traction as on

the flat.

SECTION 3

ABOUT THE ROAD

3.1

LINE

The path taken through a turn is known as the

line

. There are many possible

line

s througha turn (watch a beginner session at one turn to get an idea

how many), but there are very few correct

line

s through a turn (watch professional racers take the same

turn). Schools usually teach what is known as the qualifying

line

, the fastest, safest

line

around a racecourse without worrying about such subtletiesof racing as

passing, or keeping from being passed. This section discusses the

principles behind choosing the proper

line

.

3.1.1

THE APEX

Here we come to different uses of

apex

. The word can mean where your wheels touch (or get closest to) the

inside of the turn. It can also be used to describe locations on the

turn.

The middle of the turn is known as the geometric

apex

, the area on the inside of the turn before the center is known as an

early

apex

, after the middle is a late

apex

.

3.1.2

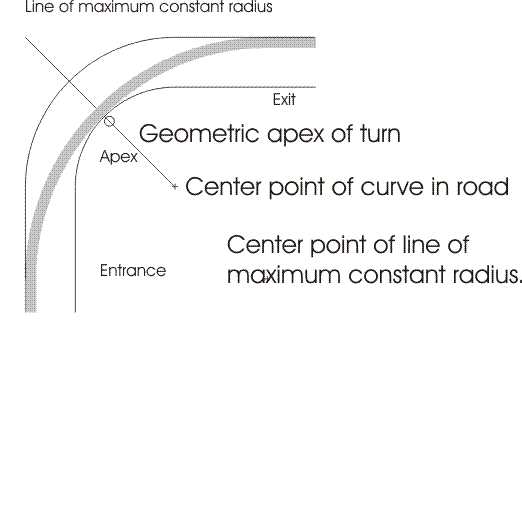

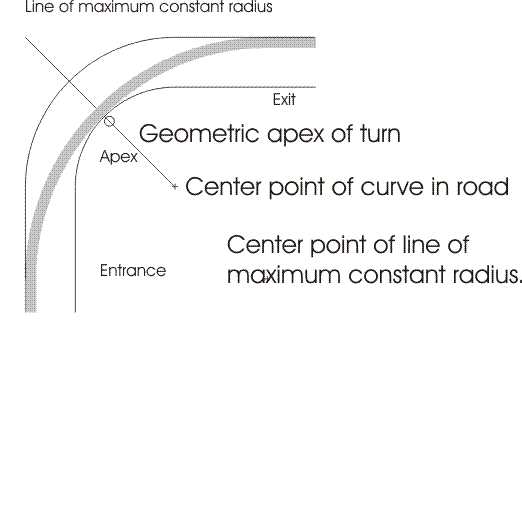

MAXIMUM CONSTANT RADIUS (MCR)

The first principle of maximizing speed through a turn is to make as

wide of an arc as possible. A physicist would say that

lateral

acceleration

is inversely proportional to the radius of the turn and directly

proportional to the velocity squared

. A non-physicist would say that the wider you make the turn, the

faster you can go. If you were to drive the largest possible circular

arc through a turn you could, you would be able to go through the turn

at the highest constant speed. This is the Maximum Constant Radius

(MCR)

line

.

To drive the MCR

line

, enterthe turn at the extreme outside edge of the road and turn the

wheel before the road itself turns. The inside wheels will touch the

inside of the edge of the road at the middle of the turn.

<DIAGRAM: mcr>

3.1.3

LATE APEX

While the MCR is the fastest

line

through a turn, maximizing the exit speed from a turn is usuallythe

fastest way to get around the track. To maximize your exit speed, you

will usually drive what is known as the

Late Apex Line

. Slow down more at the beginning than you would with a MCR

line

. This lets you to turn the car more sharply at thebeginning of the

turn so you can make the later part of the turn wider. The wider turn

means that at the same limit of handling the car can be going

faster. Two ways of telling how well this works is to notice that you

can start accelerating while you are still in the turn, usually even

before the

apex

. The other way is to look at your speedometer at the exit of the turn

and see how much faster you go when you do it right.

<DIAGRAM: late>

3.1.4

VERY LATE APEX

If you

apex

too late, the car's speed will not carry it all of the way to the

outside of the track on the exit. The problem with this is you have to

slow down more at the beginning of the turn to make it to such a late

apex

.

This is done deliberately when it is desirable to exit a turn, yet

stay to the inside, for example when we decide that it is worth

sacrificing a little speed in the first portion of an ess curve, which

looks like the letter 'S',

in order to accelerate sooner and be able to exit the second turn in

the ess at a higher speed. (See section 3.3.6) It is also a common

way of setting someone up for a pass on the straightaway following a

turn.

<DIAGRAM: rtnocar>

3.1.5

EARLY APEX

If you

apex

too early, then at the end of the turn, your car will be pointing at

the outside edge of the track. And one of two things will happen: You

will drive off the outside of the turn, or have to turn the car even

tighter to stay on the track. But, if you slow down in the middle of

the turn, the transfer of weight (and hence traction) from the rear

wheels to the front could cause you to spin.

<DIAGRAM: early>

3.2

CLASSES OF TURNS

In his book,

Driving in Competition,

Alan Johnson categorizes turns as class-one, class- two and

class-three. ����������

Even the windiest race tracks actually have far more straight road

than curved. The straights are where the cars can go the fastest. It

makes sense to choose a

line

that lets you go the fastest where you spend most of your time.

Class-one turns, which lead onto straights, are therefore the most

important. Every mile an hour that you have going into a straight, you

carry all the way to the next turn, or until the car reaches its

terminal velocity. Optimize your exit speed on class-one turns.

Class-two turns are those at the ends of straights. The longer you can

carry your speed into it, the more time you can spend going faster.

Class-three turns lead to another turn. They are is important for

setting up the turn that follows. The

line

through a class-three turn should be chosen to maximize the exit speed

from the last turn in the sequence.

When planning your

line

around the track, first identify all the class-one turns and figure

out what you must do to maximize your exit speed from them. Then look

for the class-two turns and decide how deep you can carry your speed

into them, without screwing up the

line

through class-one turn thast follows. Then you should find the fastest

way through what is left.

Note that while a turn which connects two straights might be

considered both a class one and a class two turn, it should be treated

as a class one turn. It is far more important to carry the extra speed

the whole length of the straight that follows, than the short distance

between the early and late barking points.

Occasionally you will encounter an extremely long turn, such as the

Carousel (turn six) at Sears Point. On turns like this, treat the

entrance as a class-two turn, the middle of the turn as a class- three

turn to set yourself up for the exit, which you treat as a class

one-turn.

3.3

TYPES OF TURNS

3.3.1

CONSTANT RADIUS TURNS

The most basic turn is a constant radius turn which separates two

straights.

3.3.2

INCREASING RADIUS

A turn that starts out sharp, then widens out, is called an

increasing radius turn.

If you were to drive around the inside edge of the turn, you would

start with the steering wheel turned a lot (to go around a turn with a

small radius) and would straighten the wheel as you went (as if you

were going around a turn of a larger radius). Increasing radius turns

are very fast because as you accelerate, more road is available on the

exit. The fast

line

through one ofthese turns puts the

apex

earlier than it would be for a constant radius turn.

3.3.3

DECREASING RADIUS TURNS

A turn that starts out gentle but tightens up is known as a

decreasing radius turn

. These can be very nasty if you are not prepared because all of a

sudden you will find yourself running out of room at the exit of the

turn. On a decreasing radius turn,

apex

later than you would a constant radius turn.

3.3.4

ON-CAMBER TURNS

When a turn is properly banked (the outside of the turn is higher than

the inside) is called an

on-camber turn

. The slope of the road as you go around the turn will help pull the

car back down to the center of the track. Not only that, but the

centrifugal

acceleration

actually pushes the tires into the road (rather than parallel) helping

to push the tires into the road and improving the traction. An on

camber turn can be taken faster than a flat turn of the same radius.

A turn where the road starts to go up hill, at the bottom of the hill,

or where the hill gets steeper will act just like an on camber turn.

3.3.5

OFF-CAMBER TURNS

If the inside of the turn is higher than the outside, it is known as

an

off camber turn.

Everything that worked for you in an on camber turn is now working

against you. An off camber turn has to be taken slower than a flat

turn of the same radius.

Turns at the tops of hills act like an off-camber turn because all of

the weight (and traction) comes off of the wheels.

3.3.6

SEQUENTIAL TURNS

When there are two opposite direction turns immediately after each

other, sacrifice your

line

through the first one to maximze the speed through and out of the

second turn. Do this is by taking an extra-late

apex

in the first turn, which will allow you to set up on the outside edge

of the ENTRANCE to the second turn.

It is important that you let the car settle between the two

turns. Rather than turning the wheel from one direction to the other,

pause briefly in the middle when the wheel is straight.

<DIAGRAM: essflat>

SECTION 4

ABOUT THE TECHNIQUES

4.1

SMOOTHNESS

One of the most important driving skill to develop is smoothness. It

is necessary for using all of the abilities of the car without

attempting to exceed them. There is a limit to what each car can

do. When you are below that limit, you are throwing away performance

potential. When you attempt to exceed that limit, you crash. If you

are smooth, you can keep a car just below this limit. If you are not

smooth, you will approach this limit, then back off, approach it again

and back off again, or you will exceed those limits, which can mean

problems, time loss, and often major expenses. Even when you are not

near the car's limits, inconsistent and jerky driving techniques will

lower them.

The limits of adhesion are primarily dependent on the abilities of

your tires abilities to resist sliding or

skidding

. Tires do not approach a maximum and level off. They change

drastically when they go from a rolling contact with the road to a

sliding (

skidding

) contact. When a tire starts to

skid

, it instantly loses a large portion of its traction potential. A tire

that is just below the limit may be able to generate 500-pounds of

force, but when it breaks free, it may only be able to generate less

than 300.

Achieving smoothness is easier said than done. It does not mean

applying the controls slowly; it means not

changing them abruptly.

Control changes should be applied progressively. They should be

increased until they reach their maximum value, then decreased back to

zero. Watch a good driver: he will turn the steering wheel in one

motion till he is done, then bring it back to straight. A less-skilled

driver will saw at the wheel, making all sorts of adjustments

throughout the turn.

If you are not a smooth driver and you jerkily apply and release the

brakes, throttle and steering, the car will bounce as the energy is

released or stored in the springs. This bouncing will cause the

downward force on the tires to rapidly increase or decrease, suddenly

varying the tire-to-road traction. This makes it impossible for the

driver to keep the car at the edge of these rapidly changing limits.

Not being smooth getting on the brakes will make it hard to keep the

car heading straight while braking at the limits. Not being smooth

letting off of the brakes will cause the front of the car to bounce up

and down during turndown, causing the effective steering angle to

change as the front tires load and unload.

When braking is done properly, a passenger would have a hard time

feeling the exact instant that the driver starts to apply or release

the brakes.

As you learn and practice the different driving skills, always strive

for smoothness.

4.2

BRAKING

4.2.1

THRESHOLD BRAKING

Your tires generate the most force when they are just on the threshold

of losing traction in any direction, be it forward, backward or

sideways. This is as true for slowing down as it is for accelerating.

Therefore, to stop or slow down in the least distance, you must apply

the brakes as hard as you can without locking them up. If you brake

too hard, one or more of the wheels will lock up and the car won't

stop or slow down as quickly as it potentially can. You may also flat

spot (grind tread off small portions) of the tires, wasting expensive

rubber and reducing the tires abilities. On the other hand, if you

don't brake hard enough, you will have to take your foot off the gas

sooner, which leads to longer lap times. Either way, you end up

spending less time at full throttle.

It is difficult to tell when a wheel is on the verge of locking

up. (All four wheels rarely lock up simultaneously.) By noticing that

one or two wheels are about to lock up, you can ease off the brakes a

little bit and adjust the braking pressure to keep the overall braking

force at its maximum.

You can tell that your wheels are locking up by feel and by

sound. Since a

skidding

tire exerts less frictional force than one that is not

skidding

you can

feel for this loss of friction. You can also listen for the

distinctive sound of a

skidding

tire, which also tells you to ease off on the brakes till the sound

goes away.

At this threshold, note how the brake pedal, steering wheel and the

overall balance of the car feel as the car goes in and out of the

skid

. This will train you to be able to recognize an impending

lockup...before it happens.

If you are driving an open wheeled (formula) car, there is a very

simple way to tell if either of the front wheels are locking up. Just

look at them. Note that you want to practice seeing what the tires are

doing while looking as far down the track as you can.

When you practice threshold breaking, do it where, if you make a

mistake, you can lock up all four wheels and safely

skid

off into the dirt. On the track, pick a slow corner at the end of a

long straight that has plenty of runoff room. Always make sure that

someone won't rear-end you if (when) something goes wrong. Hit the

brakes hard enough to lock up all four wheels, then let off the brakes

until you stop

skidding

. Then put more force back on the brakes until the tires start to

skid

. Practice until you can reliably keep the car right on the threshold

of going into a

skid

.

By the way, even if you have a safe runoff, try to avoid having to use

it. When you go into the dirt, then come back onto the track, you will

track dirt, which reduces traction, onto the track, messing it up for

other drivers.

If your car has an Anitlock Braking System (

ABS

) and you can turn it off, do so when on the track. Not only can a

good driver often stop a car quicker without it, but the point of a

driving school is to learn, and you won't learn good braking technique

if you let your car do the thinking for you.

If (When) you find that you cannot slow down enough for a turn and

will have to use the runoff, remember that the car will have much less

traction in the dirt. Let up on the brakes just before you go off of

the pavement so you will not lose control as the car hits the dirt.

Straighten your wheel, because if your car is trying to stop and it

suddenly loses traction, unexpected and unpleasant things are likely

to follow. In the worst case your wheel could dig into and catch in

the dirt causing your car to flip. As long as you keep the steering

wheel relatively straight (except to avoid holes and bumps in the

dirt) until you have slowed enough to turn around, you should have no

trouble even if you play Parnelli Jones in the runoff.

Remember not to practice this where people are not expecting you to

suddenly slow down in such a dramatic fashion. Coming to a sudden stop

in the middle of the main straight with a faster car right on your

tail is stupid, but people often do stupid things, especially at

driving schools.

4.2.2

BRAKE COMPOUNDS

Brake linings come in two flavors,

street compounds

that stop well when they are relatively cold but work poorly when they

get too warm, and

race compounds

that work best once they warm up (to a point) but don't work very well

until they warm up. This is because when driving on the street you

will rarely use your brakes hard and often enough to significantly

warm them up. Therefore, for the street you will want brakes that work

well when they are cold. This is why you should not put racing

compound brakes on a street machine.

4.2.3

BRAKE FADE

If you are are using your street car with street compound brakes at a

track school, you may find the stopping ability of the car decreasing

as its brakes heat up. This is known as brake fade. If this happens,

move your

s back a little bit so you do not have to brake as hard to slow down

enough for the turns. Your lap times will increase, but this is a

school, not a race and it isn't worth the risk of losing your brakes

which could end up causing you to damage yourself and/or your car.

4.2.4

BRAKING AND BRAKE LIFE

If faster lap times and maintaining the structural integrity of your

fenders are not reason enough, another reason for smooth application

of the brakes is that they will last longer. When you slam on your

brakes after a long straight, they go from cool to very hot very

quickly. This thermal shock greatly reduces the life of the brake

materials.

Smooth application of the brakes reduces this problem. Even if you

don't mind the expense and bother of replacing brakes, many cars

(especially Mustangs) can destroy a set of brake pads in a single day

of track time. If the brakes aren't treated nicely, you may find it

necessary to replace the brakes before the day is out. If you are

lucky, you will notice the impending brake failure in the paddock,

rather than at end of a 100 mph straight as you are going into a 30

mph turn.

4.2.5

PUMPING THE BRAKES

You may find that the amount of pedal travel required before your

brakes take effect increases to the point that it is difficult to heel

and toe. A temporary remedy is to give the brakes a quick pump or two

before applying them. You do not want to push the pedal down hard

enough that the brakes actually engage, pumping that hard would cause

the front of the car to bounce up and down, making it difficult to

control. Just lightly press the pedal to the point that you start to

feel resistance and quickly release it and reapply it. This pumps a

little extra fluid from the master cylinder into the brake system,

taking up the slack that caused the excessive pedal travel.

Note that this extra pedal travel can be caused by several things,

none of them good. First of all, if your car has drum brakes on one or

both ends, they may have worn down to the point that they are out of

adjustment. Even if your brakes are self adjusting, you may be

wearing them out faster at the track than they can adjust

for. Secondly, there may be fluid boiling in your brake

line

s. Either you are using yourbrakes so hard that the brake fluid itself

is boiling, or there is water, which boils at a much lower

temperature, in your brake fluid. In either case, the pedal will

regain it ’s “hard ” feel when the brakes cool

down. In this situation, there is probably nothing that you will have

time to do at a school and you should take my earlier advice about

brake fade and brake a little bit easier for the rest of the day.

The third possible cause is air in the brake

line

s. If you have air in your lines, the pedalfeel will not return to

normal when the brakes cool down. Unlike the case of the brakes being

out of adjustment, in addidtion to excessive pedal travel, the pedal

will also feel soft. Air in the lines can be a sign of serious

trouble, and if you suspect it, you should not drive the car until the

problem has been solved.

4.3

SHIFTING

4.3.1

PRINCIPLES OF GEAR CHOICE

The two things that affect the choice of gear ratios are the engine

speed and the mechanical advantage of the driveline. The lower the

gear, the greater the mechanical advantage of the driveline. This is

like using a longer lever. Each pound-foot of

torque

applied by the engine will produce more more pounds of force at the

drive wheels, and hence better

acceleration

.

On the face of it, this would imply that if we were to just leave the

car in first gear it would accelerate better and therefore go

faster. There is a catch though. Internal combustion engines only work

within a limited range of speeds. Although most modern small cars can

comfortably drive down the road with the engine turning about 2000

RPM

, they start making good power around 4000

RPM

, their

torque

peaks around 5000, their power peaks around 5500 and they redline

about 6500

RPM

.

Torque

is a measure of force-times-leverage. You get the same 100 lb-ft of

torque

by applying 100 lbs of force to a lever foot long, or 10 pounds of

force to a lever 10 feet long. With the longer lever you get more

torque

for less force, but you have to move the lever a longer distance. The

ratio of the lever pushing to the object pushing back is called the

mechanical advantage.

Horsepower is calculated by multiplying

torque

times

RPM

times a constant that makes the numbers work out. The faster the

engine turns, the further it can push a lever in the same amount of

time, so more work can be gotten from a given amount of force.

This might make us think that by running the engine faster we could

get more power. This is only true to a point, because if you run an

engine too fast, it will break. The speed at which you start risking

breaking your engine is called the

redline.

Most tachometers have three regions, black, yellow and red. If the

tach reads in the black, the engine can turn at that speed all day

long without problems. If the tach is in the yellow, you can run the

engine at that speed for short amounts of time, but not for extended

periods. When you push the tach into the red, you risk doing

expensive damage to your engine.

What this boils down to is that (on the race track) you should keep

the car in the lowest gear possible without overly risking your

engine. On the street you will usually want to keep the car well below

redline. The higher the revs, the more stress you put on your engine,

also the more fuel you will use.

Select an

RPM

for

upshifting

. This will be your shift point. Choose it according to the relative

importance of laptimes and engine life. The more important your

laptimes, the higher the shiftpoint. The more important engine life

is, the lower. The premise is that you don't want to abuse your engine

any more than you have to; breaking engines is both very expensive and

very inconvenient. Besides, if you blow up your engine, you will miss

out on track time. Choose the shiftpoint at or slightly below the

yellow range on your tach. (What I refer to as yellow might be shown

as orange or even a dashed red line as opposed to a solid red at

redline).

As you learn the track, you will probably find a point where your car

hits your shiftpoint to go up a gear just a couple of seconds before

you must start decelerating for a turn, then shift right back down

into the gear where you are now. When this happens, you may find it

expedient to put a little extra stress on the engine for a short time

and save a lot of stress on your clutch and transmission. Ruining your

clutch is only slightly less expensive and incovenient than breaking

your engine, and a lot easier to do.

At what point should you

downshift

? If you are going uphill and the car slows down,

downshift

when it is at the point where it will be below redline in the lower

gear. Unless the gears are evenly spaced, every gear in every car will

have slightly different speed where this happens. A rule of thumb to

start your experimenting would be to use about 2000

RPM

below redline as a

downshift

point.

When braking for a turn,

downshift

while you are braking in a straight line. Use your brakes to slow the

car down, using the engine won't make that much of a difference. If

the shifting is not done smoothly it can break the wheels free, which

can be bad for you, for your car and for your nerves.

Downshift

going into the turn so your car will be in the proper gear when you

start to accelerate out of the turn. Do not shift while you are

turning because not only will it upset the balance of the car, but you

will be too busy concentrating on turning the car to do a good job on

shifting smoothly.

If you are entering a turn where you will need to

downshift

more than one gear, either go through each gear in turn, or skip the

gear(s) in the middle. The advantage of skipping gears is that you

only have to concentrate on one gearshift. leaving your attention for

other things. The advantages of going through all of the gears is that

it is easier to do correctly when you are only doing one gear at a

time. While learning, it is also good practice at shifting while

threshold braking.

If you are in a sequence of turns, it may be better to shift at a

lower

RPM

if it means you can shift in the straights between turns. This is

known as

shortshifting.

If the turn is on a steep downhill, or you have not yet mastered the

technique of heel-and-toe down-shifting (described next), you may be

better off staying in a higher gear for a turn, especially if you

would be

upshifting

after the exit.

4.3.2

MATCHING REVS

There is more to changing gears than putting the clutch in, moving the

shift lever and letting the clutch out. If that is how you shift,

whenever you change gears the car will jerk.

When

downshifting

, you should to match the speed of the engine to the speed of the

wheels at the lower gear. If you are driving a car without a

synchromesh transmission, you will have to double-clutch as described

in section 4.3.2.2 as well.

4.3.2.1

HEEL-AND-TOE DOWN-SHIFTING

Matching revs while simultaneously braking and down-shifting is a

technique known as heel-and-toe down-shifting, or just

heel-and-toeing. This is a technique where you simultaneously apply

the gas and the brake by using both ends (or sides) of your right

foot. while

downshifting

The premise behind heel-and-toeing is that when you

downshift

, you do not want the engine to suddenly decelerate the driving

wheels, which puts undue stress on your clutch, driveline, axles

etc. Also, the jerkiness could cause you to lose traction and and

control of the car.

On most cars, the easiest way to perform this technique is to place

the ball of your foot on the brake and either the heel or the side of

your foot on the gas. On many cars, you have to do it the other way

around. On some cars, it is not possible to reach both pedals with the

same foot, although most can be modified to make the heel-and-toe

possible.

Find a position that works for you, then practice just blipping the

throttle. With the car parked, the parking brake on, in neutral, and

with the engine running, put your foot in the heel-and-toe position

and quickly tap the throttle so the

RPM

rises to about 2500

RPM

, then drops back to idle. The

RPM

should not be above idle for more than about a second or two.

While braking, when you slow down enough so you should be in a lower

gear: put the clutch in, put the car into neutral, and blip the

throttle so the revs go slightly higher than the engine will be

turning at that speed in the lower gear Then, as the revs drop to the

desired speed, shift into the lower gear and let out the clutch.

downshifting" width="681" height="700">

downshifting" width="681" height="700">

<DIAGRAM: HEELTOE>

4.3.2.2

HEEL-AND-TOE DOUBLE-CLUTCH DOWN-SHIFTING

If you want to be even nicer to your car, let the clutch out briefly

while shifting through neutral. This will match the speed of

everything in the transmission with itself. Then put the clutch back

in while you shift into the lower gear. This techique is known as

double-clutching.

Eight-steps are illustrated in the diagram. Note that the brake is

being applied through the entire process. If you are

downshifting

because the car slowed down going up a hill and you need the added

torque

of the lower gear, follow the same procedure, but without using the

brake.

1) Accelerating before the turn. Full throttle, car in 4th gear.

2) Braking.

3) Disengage the clutch.

4) Shift to neutral.

5) Re-engage the clutch and blip the throttle to bring the engine

speed to where it will be in the lower gear. (Steps five and six are

only absolutely necessary in cars without synchromesh transmissions)

6) Disengage clutch and shift to the lower gear.

7) Blip the throttle to match revs of engine to the revs represented

by the current road speed in third gear.

8) Re-engage the clutch, and continue braking.

If you are having difficulty with heel-and-toeing when you get to the

track, don't worry about it. There are plenty of other things to

concentrate on. However, it is a very good thing to learn and practice

in daily driving. The ability to heel-and-toe, also eliminates the

question of whether to

downshift

before or after braking.

While it is not absolutely necessary on cars with working synchros in

their transmissions, I highly reccomend always using heel-and-toe and

double- clutching when

downshifting

. As an example of how this can extend the life of the clutch, my

street car has 130,000 miles of mostly mountain road driving and over

20 hours of track time all on the original clutch.

It is equally important to be smooth when

upshifting

. You should be able to shift using three fingers or the heel of your

hand.

<DIAGRAM: dblclch>

4.3.2.3

THROTTLE STEERING

When going through a turn, increasing or decreasing the throttle will

change the handling characteristics of the car by transfering weight

to different wheels. Letting off the gas will transfer weight to the

front tires, and the car will turn more sharply, even without changing

the angle of the steering wheel. Add throttle and it will turn less

sharply. Adjusting your

line

through the turn in this way is knownas

throttle steering

.

4.4

BEING CONSISTENT

If you can't always do it the same; then you can't always do it

right. There are two aspects to getting the car around the track as

fast as possible. Knowing where to put it, and being able to put it

there. Without the first, the second doesn't do you much good. I am

referring to knowing

exactly

where in the turn to apex, not just knowing that you have to get your

inside tires in the same zipcode as the inside of the turn towards the

middle. In other words, if you can't hit the

apex

every time, you won't be able to hit the

apex

right every time.

How, you may ask, does one always do it the same way every time? By

using reference points. Note things about the track that mark where

you want to do certain actions: where to brake, where to turn in,

where to apex or where to put a wheel. Then simply connect the dots,

smoothly.

Pick reference points that will not move. Often times a school will

mark reference points with orange cones, which although easy to see

have a nasty tendancy to get moved by cars hitting them. Find a

permanent feature near the cone to use as your reference point. There

are all sorts of amusing stories about someone using a cone as a

braking marker, then the cone was got knocked a little way down the

track by another car. Another story tells about a driver who noticed

that another used a particular rock as a braking marker, so that night

he moved the rock. And of course there is the story of the driver who

discovered that the rock he had been using as a braking marker was

actually a tortoise when he later saw it move under its own power.

While reference points are an important tool for consistent driving,

you do not want to be looking at them by the time that you reach

them. By the time that you have reached the reference point, you

should already be looking down the track and thinking about the next

several things that you will be doing. Peripheral vision and a sense

of timing are two tools for achieving this.

You can gauge how well you just took a turn by noting your

RPM

(or speed, if you have a speedometer) at the exit. You want to

maximize your speed at the exit of the turn, or sequence of

turns. Another good way of telling how you are taking a section of

track is by where your shift points are. As you start driving a

section of track faster, you will have to

upshift

sooner.

4.5

SCRUBBING OFF SPEED

One of the commonest mistakes is turning the steering wheel more than

needed. Turning your steering wheel slows you down. The more you turn

it, the more it slows you. The longer you keep it turned, the more it

slows you down. It is very important, especially in an underpowered

car, to take a single smooth

line

through the turn that allows you to turn the steering wheel as little

as possible.

As soon as you have completed your turndown in a turn, you should

unwind the steering wheel as much as you can and still clip the

apex

, and exit at the edge of the track without falling off.

On many turns, when a car is

understeering

, turning the wheel beyond a certain amount doesn't do anything but

slow you down and wear rubber off of the front tires. If you find

yourself pushing, try letting out the steering a little bit and gently

ease off of the throttle. How do you tell if the car is "pushing"?

First of all, turning the wheel more does not cause the car to turn

more. More importantly, as a car starts to

understeer

, the effort required to turn the wheel will suddenly drop. When you

feel the steering go "light" is the time to back off of the steering

just a little bit.

4.6

WHAT TO DO WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

Be smooth, drive through it, don't do anything abruptly.

The most common kinds of trouble that a student will find are: getting

off of

line

, runningout of road, finding something in the road, and loss of

traction. When things start to go wrong, don't make any sudden moves.

Especially, don't suddenly take your foot off the gas, especially in

the rain. Decelerating will transfer weight to the front wheels from

the rear, often causing you to spin. I have caused some of my most

spectacular spins by taking my foot off the gas at the wrong time.

Be very careful when you see someone off of the track and/or pulling

back onto it. He probably just scared himself silly and may not be

thinking too clearly.

If someone has a wreck, don ’t stop and help. If by chance it is

a corner (or an unsupported practice session) where there are no

corner workers you will do more good by driving back to the pits so

they can send out the emergency crew.

4.6.1

GETTING BACK ON LINE

Everyone occasionally finds themselves off the

line

. You may be passing someone, you maybe being passed, you may be

avoiding an incident, or you may simply have screwed up. The important

thing is to get back onto the

line

.

The most common situation is to

apex

the first of two turns too early, screwing up your approach for the

second. Chances are, you will be entering the turn too 'low' with no

chance of getting across the track for the normal entrance into the

turn. No problem. Brake a little early so you slow down enough to

take the turn on the 'inside'

line

, until you reach the

apex

. At this point you are back "on the line" and can continue as you

normallly would have.

If, on the other hand, you tried to get back on the

line

at the entrance, chances are you wouldhave just been set up wrong for

the turn, blown the

apex

and therefore the exit as well as the

line

through any turns following. Make the best ofa bad

line

.

4.6.2

RUNNING OUT OF ROAD

When you put two wheels into the dirt, keep your foot on the gas,

(letting off will just make you spin) and

gently

drive back onto the course. Another option, is to straighten the

steering wheel FIRST, before going off of the track. Then, when the

car is straight gently let your foot off the gas. Once you have

regained control of the car, you can either come to a stop, or gently

pull back onto the track.

Be very careful when pulling back onto the track. Remember, the guy

coming up on you might be so intent on what he is trying to do, he

might not notice you pulling out into his way. Or he may notice you,

but be too close to the limits of his car to do anything about it. A

yellow flag being displayed doesn't guarantee that the other drivers

saw it. Be aware that students are often concentrating so intently on

one thing, they can fail to notice other, far more important, things.

Look to the flaggers for reentry. If they say it's clear, double check

(if you can see) and go. If they tell you to wait, then wait until you

get the clear sign.

After you have had an off road excursion, remember that you now have

all sorts of dirt and gravel on your tires. Dirty tires do not stick

as well as clean tires. Even dirt that got on the track because

someone else spun reduces traction. Watch out for it. It is often a

good idea to pull into the pits the next time around to make sure

there are no rocks or gravel caught between the wheel and the tire.

Take your time getting back up to speed. One of the times you are most

susceptible to making a mistake is when you're already rattled from

making a previous mistake. Shake out your arms, relax, check the

gauges and drive 7/10s until your heart rate gets below 300.

It is important to remember that it is usually better to smoothly

drive off of the track and back on than to pinch off your exit trying

to stay on the track. Of course, if there is a large rut, a serious

drop-off at the edge of the track, or something to hit, then do what

you can to avoid hitting it.

4.6.3

FINDING SOMETHING IN THE ROAD

It is much easier to avoid trouble by steering around it than trying

to stop in time to avoid it. If you must slow down, signal the other

drivers by putting your hand in the air. Watch your mirrors. Make sure

that you don't get punted because you tried to avoid someone elses

mistakes.

It is just as important to watch your mirrors when making an emergency

stop on the street, perhaps more so. People driving on the street are

very prone to not paying attention to what is going on around thm.

<DIAGRAM:getting back on line>

4.6.4

LOSS OF TRACTION

Understeer

When your front wheels lose traction first, it is known as

understeer

, plowing, or pushing. The steering wheel becomes very easy to turn,

but turning it more has no added effect. The car steers less than you

want it to.

Let the steering out until turning the steering wheel takes effort

again. All that turning the wheel beyond this just slows the car and

wastes tires. Gently let off the gas to put weight, and traction, back

on the front wheels. Be very gentle and smooth, lest you over-correct

for the

understeer

and find youself in an

oversteer

situation.

Oversteer

When the rear tires loose traction first, it is known as

oversteer

, tail-happy, or loose. Point your tires in the direction that you

want to go. If you over-correct, the tail end will whip past center

and the car will try to spin out in the other direction. When you are

experiencing

oversteer

, don't suddenly take your foot off of the gas. All that will do is

transfer the weight to the front tires causing the car to spin out.

<DIAGRAM under/

oversteer

>

4.6.5

SPINNING OUT

Eventually you will find yourself in a situation where you know that

you are going to spin out. The car is

oversteering

and opposite lock is not going to help.

To regain control of the car when you spin, simply straighten the

steering wheel and depress the clutch.

Remember that tires would much rather roll forward (or backward) than

slide sideways. So, if the brakes aren't locked when the car has spun

180 degrees (you are facing backwards) it is a lot easier for the car

to roll straight backwards than to continue spinning. It is important

to depress the clutch to keep the car from stalling. When the car is

rolling backwards, you can simply drive backwards to a safe place to

turn it around.

If you want to try being fancy and bring the car back around so that

you are heading forwards again, turn the wheel to the side of the road

on which you want to end up. If the wall is to your right (while

looking out the windshield) turn the wheel to driver's left.

A simpler technique is referred to as "in a spin, both feet in". Put

your left foot on the clutch and your right foot on the brake. Your

car will come to complete stop, with the engine still running, so you

get going again as soon as traffic allows.

A rule of thumb is: If you hit the brakes, you will usually spin to

the outside. If you stay on the gas, you will usually spin to the

inside.

If a car is spinning in front of you, aim at where he is when he st,

because he probably won't be there when you get there. Cars usually

spin to the inside of the track. Be careful though, sometimes they hit

something and bounce back out. Be very carefull about lifting your

foot off the throttle lest you cause yourself to spin out.

Many spins are caused when a driver sees someone getting into trouble

in front of him , and lifts off the throttle to slow down. If the car

is on or near it's handling limits, when the weight comes off of the

rear tires, the available traction becomes less than the traction

being used and then

two

cars are spinning.

.4.6.6

IF YOU HAVE MECHANICAL PROBLEMS

When the car is acts up and slows down, put your hand in the air to

warn the other drivers.

Don't stop in the

line

orin an impact area. If there are a lot of

skid

marks pointing to where your car is parked, it is not a healthy place

to hang out.

Try not to get stuck in mud or sand. If you pull off of the course, do

it where you will be able to get back on safely.

Do not park in tall, dead grass. Hot exhaust pipes and catalytic

converters are excellent fire starters.

Before taking your car to the track, make sure it has tow points so

that the tow crew can pull it without damage. Be pleasant to the tow

crew; it isn't their fault that your car broke, or you crashed.

4.6.6.1 IF YOUR CAR GOES DEAD ON THE COURSE

If your car is dead on the track, or in an impact area, unless it is

on fire, stay put and keep your helmet and belts on until you receive

instructions from the corner worker. The car is much better protection

from other cars than is a driver's suit.

Do not work on or inspect your car unless it is well protected. It is

much better to lose track time, than be run over because someone lost

control of their car while you were working on yours.

When you get out of the car, get out on the side away from

traffic. Get well back from the edge of the track. Do not let the

barriers give you a false sense of security. Cars, and at the very

least, parts of the cars can easily go flying over the barriers in a

high speed impact. To quote a flagging trainer: "There is no place on

the track a car cannot go, only challenges not yet met".

4.7

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FRONT AND REAR-WHEEL DRIVE

There is less difference between driving the two than many people

think. Front-wheel drive cars tend to

understeer

more than rear-wheel drive, but some rear-wheel drive cars plow worse

than some front-wheel drive cars. You won ’t need to worry about

the subtle details. Most drivers who are new to the track, take

several track days to just become able to get their cars consistently

within walking distance of the

apex

. The minor difference in the ideal

apex

for each type of car is not important at that point.

4.7.1

POWER UNDERSTEER

One of the differences between a front-wheel drive and a rear-wheel

drive car is power

oversteer

vs. power

understeer

. In a front-wheel drive car , if you apply too much power in a turn,

you will experience power

understeer

. Your steering will become very light and will have little

effect. This is a bad thing.

If this happens, keep the front wheels pointed in the direction you

want to go. When the front tires regain traction, the car will

suddenly accelerate in whatever direction they are pointing. If the

wheels are pointing at the side of the road, or another car, bad

things could happen.

The appropriate response to power

understeer

is to gently let off of the throttle while letting out some of the

steering until traction is regained. When you exceed the front tires'

abilities, turning the wheel more will only slow the car down and

waste expensive rubber.

4.8

DRIVING WITH AN OPEN OR A LOCKED DIFFERENTIAL

There are three types of differentials, open, limited slip, and

locked. An open differential allows the wheels to turn at different

speeds when going around a turn. Unfortuaatly, if a wheel loses

traction, as when the inside wheel comes off of the ground, no power

will be applied to the wheel that still has traction. A locked

differential acts like no differential at all. Both wheels will turn

at the same speed, as if they were on a solid axle. This makes it

harder for the car to go around turns, because one of the wheels will

be scrubbing against the pavement. A limited slip will allow the two

wheels to turn at different speeds, within limits. This allows the car

to easily go around turns, and still get power to the road when one of

the wheels does not have any traction. The problem with limited slip

differentials is that they are expensive.

Carroll Smith has an excellent discussion of differentials at the back

of "Drive to Win".

4.8.1

OPEN DIFFERENTIAL AND SOFT SUSPENSION

Most street cars have open differentials and relatively soft

suspensions. What this means, is that if you are cornering hard and

the inside wheel comes off the pavement, the wheel will spin freely if

you apply the throttle. If you find yourself unable to get any power

to the ground when you are exiting a turn, try taking a later

apex

line

. By slowing down and turningdown more at the beginning of the turn,

the car will be cornering less hard at the exit, which will help keep

the inside wheel on the ground.

4

.8.2

LOCKED DIFFERENTIAL

��������������

Since an open differential can be converted to a locked differential

with about $0.50 worth of welding rod, it is a common performance

modification. Although this will solve the traction problem of an open

differential, it causes some problems of its own.

The first problem is that cars with locked differentials want to go

straight. This makes it tough to get the car to turn down. It may be

necessary to trail brake (see section 4.10) more than if the same car

had an open differential. On the plus side, since both driving wheels

want to turn at the same speed, the car will be very stable under

acceleration

, making it very easy to "plant" the rear end in rear-wheel-drive car

by accelerating out of a turn.

The other downside of a locked differential is that since power can

get to the outside wheel in a turn, it is easier to break the outside

wheel free in the rain, which can cause a spin in a rear-wheel drive

car.

4.9

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

The next few pages cover how to drive the late

apex

line

through a turn. (It does not cover the details about why. They are

covered in section 3.1.)

Study both the small and the large drawings in this section.

The small drawings in the margins show the weight-balance and the

acceleration

vector drawings for their associated paragraphs. They show what is

happening to the car at each of nine phases of the turn.

The two full-page drawings show the

line

through a right angle turn and a hairpin turn, illustratingwhat is

happening to the car during each phase. The position of the car at

each phase is indicated by a miniature of their balance-vector

drawings.

The circle in the center of each drawing of a car represents the

circle of friction

, or the

acceleration

potential, of the tires. For simplicity, we will assume that the tires

can generate the same amount of force in any direction. The arrow

within this circle represents the

acceleration

vector of the car. If the car is speeding up, the arrow points

forward. If the car is braking, it points to the rear and if the car

is turning the arrow points to the side. Note that at no time can the

arrow extend outside of the circle.

The car used in the example can only accelerate at half the ability of

the tires, which is a reasonable model of most street cars. While some

cars can spin their driving wheels when driving in a straight

line

just byputting on the throttle, most cannot.

The amount of downforce on each tire is shown by the size of the

circle that represents that tire. The more downforce on the tire, the

larger the circle. Note that the weight transfers away from the

acceleration

vector. A car that is speeding up will have more weight on its rear

tires. Keep in mind that the greater the force pushing down on a tire,

the greater the sideways force it can generate.

Although passing in the turns is not allowed in the beginner's section

of most schools, you should watch out for it anyways. People break the

rules. You should be aware of where the other car is, lest you hit

someone who is passing you. Eventually, you will be driving in

sessions where passing in the turns is allowed. It is better to

develop good habits early than to try to break bad ones later.

While I break the turn up into discrete steps, in reality they all

blend one into the next. Concentrate on smoothly connecting each

phase of the turn so that they blend into on smooth and flowing

manuever.

4.9.1

SETTING UP FOR THE TURN

A) Before the turn,

line

the car up all the way at the outside edge of thetrack. Check your

mirrors, don't pull into someone who is trying to pass you on the

outside. If someone is immediately behind or in front of you (in a

school) brake a little early to give yourself room in case their car

cannot stop as quickly as you.

While you are preparing to brake you should note where your

braking point

is going to be. You should not look at it again until the next lap.

B) When you take your foot off the gas, weight will transfer to the

front wheels. Do this smoothly so that the car does not bounce up and

down. Let the car settle for just an instant before applying the

brakes.

4.9.2

BRAKING

C) By the time you reach your

braking point

, you should be looking through the entrance portion of the turn to

the

apex

. One of the skills that you need to develop is an awareness of where

you are so you can do things at the same place every lap, without

looking at your reference points. At your braking reference point,

apply the brakes. Quickly, but gently, squeeze them on until wheels

are on the verge of lockup.

(In section 4.3.2.2 is a discussion of heel-and-toe

double-clutching. For most manual transmission cars it is the

smoothest way to slow down for a turn. If you can learn and practice

it before going to the track, do so. If you do not know heel-and-toe

braking when you get to the track, do not try to learn it along with

everything else.)

If you don ’t heel and toe, you will need to brake earlier, to

give yourself time to

downshift

between braking and turning down. When you

downshift

, do so quickly to minimize the time when you are neither braking,

accelerating nr turning. Even if you don't heel-and- toe, you should

match the revs on a

downshift

by blipping the throttle while you shift through neutral.

D) When you take your foot off of the brake, weight transfers from the

front to the rear wheels. Do this smoothly so that the car does not

bounce up and down. While you do not want to coast for a long time

going into the turn, wait an instant between letting off of the brakes

and turning the wheel to let the car settle.

4.9.3

TURN-DOWN

E) Before you turn down, make sure that there is not a car where you

want to go. By this point you should be looking past the

apex

to the exit. So the trick is to know where the cars around you are,

while looking further down the road. Do this with your peripheral

vision and a quick check of your mirrors.

The place you start turning the steering wheel is called your turndown

point. Since turning the wheel will scrub off speed, spend as little

time with the wheel turned as possible. Wait as long as you can to

turn your car and still make it to the

apex

. It also means you should dial in your steering as quickly as you

can smoothly do so, so you waste as little time as possible in

transition.

4.9.4

APEX

F) By the time the car is a little past one-third of the way through

the turn, it (technically the inside wheels) should be aimed at the

apex

. The correct

apex

for a turn will usually be between one-half and two-thirds through the

turn.

When the car is aimed at the

apex

, let out the steering as you apply the throttle. A low powered car on

a dry track will often be able to use full throttle by the

apex

. Be carefull though, too much power could cause the driving wheels to

lose traction, possibly causing the car to spin out.

There are two things to keep in mind about an

apex

. The first is where you

apex

the turn, i.e. where the car is when it reaches the point where it is

closest to the inside of the turn. The second is the direction the car

is facing when it reaches the

apex

.

How deep into the

apex

should you go? As deep as you can without upsetting the suspension of

your car. The closer to the inside of the turn you are, the more track

you have to the outside, and the faster you can take the exit. Leaving

any space between you and the edge of the track at the

apex

is effectively just throwing away that much track on the

exit. However, putting all four wheels into the dirt on the inside of

the turn will probably just do nasty things to the tires, the

suspension, and possibly the bodywork.

Most racetracks have concrete

berm

at the insides of the turns. This concrete protects the edge of the

track to keep the asphalt from crumbling as cars drive right on the

edge of the road. The softer a cars suspension is, the more it will

lean and the less weight will be on the inside wheels. In the some

cars one of the inside wheels will be off of the ground. Therefore the

softer a cars suspension, the higher on a

acceleration

you can drive.

If you hit the

acceleration

in a car with a very stiff suspension, you will upset the suspension,

launch the inside wheels into the air, and end up going slower through

the turn.

Either way, when you hit the

acceleration

just right, you will feel a slight bump. Not enough to upset the car's

suspension, just barely enough to notice.

On your warm-up and cool-down laps, when you are not driving all out,

it is a good idea to solidly drive up on the

berm

. This helps you learn exactly how wide your car is, and exactly

where the

berms

are.

A NOTE ABOUT THE PAINT ON THE BERMS

These

berms

, and about eight inches of track next to them, are usually painted

red and white. This paint does not give as good traction as does bare

asphalt. In the dry, there is so little weight on the inside wheels

that this does not cause a problem. Therefore, in the dry, you should

put your inside wheels well onto this paint.

However, in the wet, his paint becomes one of the best

friction-reducers known to mankind. Careless application of throttle

with your drive wheels on the paint will cause an immediate loss of

traction. With many rear-wheel drive cars this will almost guarantee a

spin. In the wet, put your wheels right next to, but not on the paint.

You should be aware if anyone is trying to pass you on the

outside. When this happens, keep the car close to the inside edge

longer, making it a very late

apex

in order to exit the turn without hitting the other car.

4.9.5

EXIT ��

G) Will blend into H.

H) Once past the

apex

, you should be increasing throttle and unwinding the

steering. Remember, turning the steering wheel is like putting on the

brakes. The more the wheel is turned the slower you will go. At this

point in the turn you are entering the straight and should be treating

it as such.

I) Your speed should carry you all the way to the outer edge of the

track at the exit. You should finish unwinding the steering wheel when

your car reaches the outer edge and your wheels (and car) should be

pointed down the straight.

Except for the situation where you are sacrificing the ideal

line

in one turn to set up forthe next, you should always exit all the way

to the edge of the track,

even if your speed does not carry you all the way out

. There are two reasons for this.

The first reason is that as your technique improves, your increased

speed will be carrying you to the edge of the track. It is best to

learn your

line

s putting the car where it will eventually be.

The second reason to use the whole track is the tighter your steering

wheel is turned, the more speed you will scrub off. Therefore the less

you turn your wheel and the sooner you straighten it, the faster you

will go. Get into the habit of using as little steering as possible.

Look at the difference between the

line

of maximum constant radius and the late

apex

line

. Note how turningsharper earlier in the turn lets you accelerate

during the turn rather than waiting until the car is on the straight.

DIAGRAM: RTWCAR >

<DIAGRAM hairpin>

4.10

TRAIL BRAKING

If you have a car that

understeer

s, use trailbraking to improve its ability to turn down. By trailing

your braking deeper into the turn you keep weight on the front tires

during turndown, making the car turn in better.

Trail braking also has the advantage of allowing you to wait a little

longer before you have to start braking.

Just before the turn-down marker, start releasing the brakes. As you

turn the steering wheel, release the brakes more and more. The

steering wheel should be turned the most just about as the brakes are

all the way off.

Trail braking is an advanced technique. Wait until you have had a day

or two of track time before you try it. Even if trail braking would

help your car's handling, all not trail braking will mean is that you

will need to slow down a little bit more under straight line braking

to make the turn.

There is another technique known as the "confidence lift". When a car

has the handling to take a turn at full throttle, but has difficulty

turning in at full throttle, you can briefly lift your foot off the

gas as you turn in.

However, people will often lift at the entrance of the turn, not

because the car has trouble turning down, but because they have

trouble convincing their foot to stay down. When this happens, try

this trick. Lift your forefinger from the steering wheel. This often

fools the brain by making it feel you are lifting your foot, while you